Dancing in the Streets: A History of the Second Line

Whether you’ve been to New Orleans or not, you’ve seen them—the brass band that parades through the streets in a somber march only to erupt in a celebration of music, color and dance. Like the pied piper the band draws crowds who dance through the streets like it’s Mardi Gras.

That is the Second Line.

So what is a Second Line exactly?

In this episode of World Footprints, Tonya and Ian Fitzpatrick visited The Historic New Orleans Collection (THNOC) in the French Quarter to meet with two amazing guests, Judy Cooper and Eric Seiferth, who help us understand the history and traditions of the Second Line.

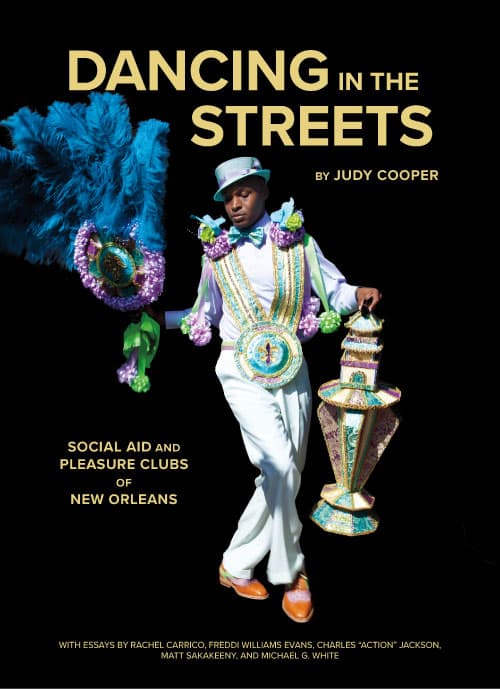

Judy Cooper is a long-time New Orleanian and second-line photographer who has just created a vibrant photo essay book on the second line entitled, Dancing in the Streets: Social Aid and Pleasure Clubs of New Orleans (published by The Historic New Orleans Collection). Judy’s book explores and celebrates the Second Line’s history and practice.

Eric Seiferth is curator and historian at The Historic New Orleans Collection focusing on 20th-century New Orleans and the musical heritage of the city. Eric co-curated the Collection’s “Dancing in the Streets” exhibit which is available online at HNOC.org.

Put on your alligator shoes and Sunday best as we explore the history of the Second Line while we go dancing in the streets of New Orleans.

* * * * * * * * *

If you enjoyed this episode we have a favor to ask:

Please support World Footprints by leaving a 5-star rating and review on Apple podcasts or your favorite podcast platform. This will help other likeminded and interested travelers find us.

Also, please join the World Footprints community by subscribing to our newsletter on World Footprints.

Full transcripts are available in the link below.

Book Your Stay Now in New Orleans

Use the interactive map below to search, compare and book hotels & rentals at the best prices that are sourced from a variety of platforms including Booking.com, Hotels.com, Expedia, Vrbo and more. You can move the map to search for accommodations in other areas and also use the filter to find restaurants, purchase tickets for tours and attractions and locate various points of interest!

Guests:

Tonya (00:12) Welcome. You’re listening to World Footprints. I’m Tonya Fitzpatrick. Ian (00:17) And I’m Ian Fitzpatrick. On today’s episode, we’re going to dance through the streets of New Orleans as we learn about the history and practices of the second line. Judy (00:27) The first line would be the family, the family themselves and the band. And then the second line was the name for all of the mourners that would follow along behind. And the way the old funeral went was that they played somber dirges and hymns on the way to the Cemetery. And when they got to the Cemetery and after the burial on the way out of the Cemetery, the band would start playing more lively tunes. And the second line folks would start dancing as a celebration of life. Tonya (01:13) You just heard Judy Cooper, a longtime New Orleanian and second line photographer, explain where the term second line came from. Judy recently published an amazing photo essay book about second line history and practice called Dancing in the Streets: Social Aid and Pleasure Clubs of New Orleans. Ian (01:35) During a recent visit to New Orleans, we stopped by the historic New Orleans collection in the French Quarter. That’s where we met Judy Cooper and Eric Seiferth, a historian cocurator of the collections Dancing in the Streets exhibit. Tonya (01:50) Judy and Eric, welcome. Thank you so much for joining us on World Footprints. Eric (01:55) Thank you for having me. Judy (01:56) Yes. Tonya (01:58) I love the work that you’ve done about the second lines. And I want to ask, first of all, Judy, what is a second line? Judy (02:07) A second line is a street parade with a brass band. And these are clubs, the social Aid and pleasure clubs. They call themselves in the city. There are about 50 of them, and each one parades once a year on a set date. Tonya (02:30) I think a lot of people may confuse the second line with Mardi Gras Indians. Are they one in the same, or are they distinct? Judy (02:38) They are totally distinct. Totally distinct. These are as I said, they’re social aid and pleasure clubs, and each one will put on a parade once a year. They get all dressed up. The men wear either very colorful suits or shirts and pants and matching hats and shoes and gloves and carry big fans and other paraphernalia that they wave as they dance through the streets to the music of a brass band. And one of the unique things about the second line parades is that the spectators don’t just stand on the sidewalk and watch them go by. They fall in behind the band and everybody dances through the streets for 4 hours on a Sunday afternoon. Tonya (03:32) I couldn’t imagine standing still. Judy (03:35) The music you can’t even me as a photographer, I couldn’t stand still. Tonya (03:41) So, Eric, what is the back story, the second line? How did they start? Eric (03:45) Well, there’s a long tradition in town of parading and musical processions. It goes back really to the founding of the European city here in the early 18th century. If you fast forward a little bit to the 19th century. There are a lot of different kinds of voluntary organizations specifically for African Americans, Afro Creoles in the city. I say voluntary. These are like benevolent associations or mutual aid associations, meaning they are members provide each other with social services. They meet and have events as well. And they’re also a number of fraternal organizations. These groups continued throughout that century. And after the Civil War, of course, you get an influx of a new population of African Americans in the city, particularly leaving the plantations and coming into urban areas. It happens across the South, and it results in explosion of clubs of this kind. And this is happening in the city among all different types of groups. There are women’s literary clubs and social clubs. There are unions forming. There are all kinds of fraternal organizations. We think by around 1900 there’s something in the order of 200 to 300, specifically black clubs made up of Afro Creoles and African Americans in the city. Eric (05:26) And a lot of them start parading as one of their events, whether it be an annual parade. They may put on funeral parades when somebody passes away. We know, for example, one of the oldest current club that still practices Young Man Olympians Junior. They date to the 1880s, and their founder tells us that their parading tradition started with funeral parades put on for the musicians in the club. And after a while, they embraced having annual anniversary parades to celebrate the anniversary of the founding club. Another example from that period comes from economy hall. And I know you’ve talked with Fatima and I don’t know if she mentioned this, but in the club minutes that she has in the 1870s, you can see in French them talking about having an annual parade is one of their main events. And they say, well, what kind of music should we have for the parade? And they kind of stumble around a little bit with the language, but end on brass band in English, there’s no French word for kind of this type of music. So that really shows this kind of French American–African influence coming together to form this unique style of performance and this unique style of procession and celebration. Eric (06:52) So those just kind of continue and they grow into the 20th century in different ways, but that’s kind of the foundation of the clubs which make up the backbone of second lines. Ian (07:07) Judy, as a photographer, your book Dancing in the Street captures this rich culture, this rich history, and brings it to life in ways that perhaps haven’t been seen. What attracted you to the second line to these social clubs as the subject for this book? What was it about it from the photography or the photographic eye that brought you to this? Judy (07:41) Their color. I actually have always liked to photograph New Orleanians’ characters, and one of the main aspects in New Orleans is the love of dressing up or costuming for almost any occasion. And so I thought when I found out about their costumes with their fans and just how colorful they were, and then the movement, the dancing is wonderful, the vitality and the joy. Tonya (08:12) And who is this pictured on the cover? What club is this? Judy (08:16) All right, this is a club that calls themselves the Old and New Style Fellas. And the Old Part is that they don’t wear suits. They wear pants with shirts. And in the old days, they wore colorful suspenders. The original costumes were pretty much less elaborate. Well, so this is a yoke instead of suspenders, then the hats and the shoes and then this wonderful feathered fan. And then this is a variation on a cane. The original fellows would maybe carry a cane that they would decorate with ribbons. So this is all based on the really old traditions. This fella, Tyrone, Trouble is his nickname. Tonya (09:15) Wonder why. Judy (09:16) And he designs every bit of that costume. And his club members. It’s a family oriented club, makeup by hand. This is brocade, all sorts of stitching. And it’s amazing. Tonya (09:38) Actually, I was going to ask you if they handmake these like kind of the Mardi Gras Indians do with their costumes, and I think they change them up. The Indians change their costumes every year. Did the second line clubs change their costumes? Judy (09:55) Absolutely. Tonya (09:56) Every year. Judy (09:58) Something new. As a matter of fact, they parade in the spring. As a matter of fact, they’re next Sunday. And they had their outfits ready in 2019. But their parade was canceled. Trouble’s mother Sue is sort of the President of the parade. And so she said when they finally got to resume parading, well, let’s just use the ones we already had. And he said, Are you kidding? That’s not new. So they’re having all new outfits. Tonya (10:32) Oh, my goodness. Judy (10:33) For next Sunday. Tonya (10:34) What do they do with the old outfits? Do they auction them off to raise money? Judy (10:39) A variety of things, but their closets are full of stuff and their attic, too, I think. Actually, I’ve been to Sue’s house and they have bunches of those just standing around. And the shoes, they sometimes wear the shoes later. And those shoes, they like alligator shoes. Almost all the clubs get alligator shoes and they get them custom made, usually in either Spain or Italy. And they cost up to $1,000 a pair. Tonya (11:10) And they get new shoes every year. Judy (11:12) New shoes every year, yeah. Announcer 1 (11:17) This is the award winning World Footprints podcast with Ian and Tonya Fitzpatrick. World Footprints connects you to the world through powerful storytelling that uncovers the full narrative of our cultural and human experiences. Support our work by leaving a five star rating and review on Apple Podcasts or wherever you’re listening to us, so you can help other like-minded listeners find us. Also, visit Worldfootprints.com and subscribe to our newsletter for travel resources, news and event information. Tonya (11:49) “A second line is, in effect, a civil rights demonstration, literally demonstrating the civil rights of the community to assemble in the street for peaceful purposes, or more simply, demonstrating the civil right of the community to exist.”–Ned Sublette. Here’s more of our conversation about the history of The Second Line with photographer Judy Cooper and historian Eric Seiferth. Ian (12:17) Eric, one of the things that strikes me about this particular piece of New Orleans life is that it’s focused on family and it’s focused on community. And even though the number of clubs have dwindled over time, why do you think it’s held on? It’s been able to survive for so many generations. Eric (12:41) I think you nailed it. It’s the family aspect and the tradition of going out on Sundays in the afternoon to see a parade, even if you’re not in a club, is just pervasive. It’s addictive, too. You go out on a Sunday on a beautiful day and you can smell the barbecue, get yourself open to drink. You see everyone’s just seeing each other catching up. I haven’t seen in a couple of weeks what’s going on. They’re different clubs that aren’t parading talking about their plans. And then the parade starts and you have the music and the club comes out and you see what they’re wearing for the first time. I mean, I think that it just is such a wonderful experience that it grabs people in the city and they want to keep being a part of it. But the family aspect is really important, too. And you’ll see kids and a lot of clubs have kids divisions, so some of the clubs will have enough members that they’ll have multiple divisions. A division might be ten to twelve people, and each division gets its own brass band and they come out separately. And a lot of the clubs have kids divisions where you’ll see six, seven, eight year olds dressed up like everybody else in dancing and doing all the moves. Eric (14:09) And it’s just really cool to see. And so they grow up in the tradition. This is their tradition coming out on a Sunday and spending the year together getting ready for the parade. And yeah, I think it’s really important for the people who are kind of the leaders now, people like Sue Press, Linda Porter of the Lady Buckjumpers and so many other club leaders to inculcate the kids in the tradition so that it’ll continue continuing is really important. We saw that in the exhibition and in the book. When we talk to clubs, continuing the tradition was of utmost importance. So it’s really a big part of it, too. And they do outreach to schools and to the kids in the community, raising fundraisers for backpacks with school supplies or whatever it is giving out Turkey dinners on Thanksgiving, which is something Sudan has done in the past. So there’s a connection with the community, too, that helps and connect with the kids in the communities that they’re a part of. So all of that is kind of the glue that keeps it going over time. Ian (15:28) These costumes are so flamboyant, so colorful, and I can imagine there’s, like a healthy rivalry amongst the clubs here as to who can outdo the other. I wonder how that’s played out in terms of seeing how the clubs stay at the cutting edge and or upping their games year after year. Judy (15:51) There is definitely and that’s one of the reasons that all of the clubs go to each other’s parades so they can see what they’re wearing. There is one club, the Uptown Swingers. It’s the last parade of the year at the end of June. And the President, he designed him to help make the costumes. And he says we’re the last parade, and they’re going to be talking about us till next year. So proud of that. And the color of the outfit is a very closely guarded secret. Nobody is supposed to know it until they come out that door at the beginning of the parade. Tonya (16:35) As many of us know, gospel music has its roots in the African American spirituals sung by enslaved people. And the spirituals enabled the enslaved to communicate and share information with each other because they weren’t allowed to talk to each other in the cotton fields. Ian (16:53) So we asked if the second line also had its roots in the oppression of black people. Eric (16:58) Well, that’s a great question and a complicated answer, but I think one of the things that is really powerful in the second line tradition is this idea of taking civic space and taking ownership, particularly in places that otherwise are off limits. So you see this going back centuries where specifically, if you think about Jim Crow just after Reconstruction is over and there’s a repressive regime to reassert white supremacy, and these clubs are forming and they’re going out into public space performing loud music and asserting their control in their part of civic life in the city. And it continues into the 20th century. And I think that part of the tradition remains. I think it’s really powerful. You see it going back further, even to Congo Square, right when people are gathering in the city and taking space. There’s another two moments that I think are really interesting that I’ll mention briefly that happened during the Civil War in New Orleans. And one of them is a funeral for an Afro Creole soldier. And his funeral procession includes all these different clubs. He was part of a voluntary association of a club, a few clubs, actually, and they wind all through the city with music. Eric (18:48) And we have images of this. And in fact, it’s reported as far away as New York and The New York Times. This funeral and this funerary tradition continues to this day. Just a few years later, there is a large parade to celebrate emancipation in the city. And this comes in 1864 here in New Orleans. And the parade again is made up into divisions with bands and fraternal organizations, mutual aid organizations, school kids, and they go all through town performing music and having this amazing procession. So I think that that aspect of it is one of many related to how systems of slavery have impacted the second line practice. But it’s really an interesting and powerful one. Tonya (19:49) I know you just had an exhibit. I’m wondering if you can share. What did we miss? Eric (19:57) Oh, yeah. Well, we put on an exhibition, Dancing in the Streets, and came with the book, opened in February of last year and ran for about four or five months. We looked at kind of this history. We had images of that funeral I mentioned. We had film of parades from the 60s, photos from the back to the 40s of parades. And then we talked about some of the different clubs, like the YMO. And we worked with 30 different club leaders on this project and culture bearers, including two, Sylvester Francis, who operated the Backstreet Cultural Museum in Treme, and Ronald Lewis, who had a Museum in the Lower 9th Ward, the House of Dancing Feathers. We work with both of them as well, as I should mention, Action Jackson. All three of them have since tragically passed away. So we dedicated the project to them. We had items from their museums. They were really the first people to create Museum spaces around this history and culture, so we wanted to honor them in our display. If you go online to HNOC.org/secondlines, you can see the products that we’ve made that exist outside of that exhibition. Eric (21:33) So there’s a virtual exhibition where you can see some of the items and hear club members talk about the history. We produce 30 club narratives where the club leaders tell the stories of their clubs, and you can read those narratives and learn about those clubs. So there’s still a lot online. And, of course, the book. And so we kind of created this large community of people working on this project, from Judy to the clubs we worked at, the Neighborhood Story Project. It’s another local organization and those two museums I mentioned. So it was really an amazing experience that we were able to continue through the struggles of the pandemic, which stopped the second line. But we got through. Tonya (22:25) Well, I’m so grateful that you both preserve this important history for all of us to enjoy. And I’m very grateful that the exhibition is available online as we wrap up, because we are a socially conscious travel show, I have to ask you a travel related question–either of you–and I’ll ask each individually. If you could travel to your favorite country and sit next to anybody you want, past or present, who would that be? Eric (23:04) You want to go first? Judy (23:05) No. Goodness. Eric (23:09) Oh, my gosh. Yeah. I don’t know where to start. Judy (23:14) France is one of my favorite countries, but I can’t think of who I would want to talk to necessarily right off the top of my head. Tonya (23:23) The first person who comes to mind is the right answer. Eric (23:33) Yeah. Oh, that’d be nice. That’s a good one. I love traveling to France as well, I haven’t been anywhere in so long. Sadly, the last place I went, I had an amazing experience with Sicily. I’d love to go back, and I’d love to spend dinner on a family farm and have a meal with somebody whose name we don’t know but who was important in that time. Tonya (24:09) And what is that person’s name? Eric (24:12) No, I don’t know. Just an everyday person to experience the life on their farm. Judy (24:25) Well, it would be kind of fun to go to Italy and talk to Leonardo, for instance. Eric (24:29) That’d be a good one. Yes, that would be a good one. Tonya (24:33) Well, thank you both so much for joining us, for sharing your craft and for giving us something to reflect back on and see where traditions, very strong traditions in New Orleans and probably beyond have started. Thank you. Eric (24:52) Thank you for having us. Judy (24:54) Thanks for your interest. Tonya (25:02) I’m so sorry we missed the Dancing in the Streets exhibit, which closed just before we arrived. But for everyone, the exhibit is available online at hnoc.org–that’s The Historic New Orleans Collection dot org. I want to thank The Historic New Orleans Collection for hosting us. This facility, this campus is really a gem that’s hidden in plain sight within the French Quarter. Ian (25:35) Plain sight, yes. But it’s because of the way that the buildings are scattered throughout. Sometimes you don’t recognize that they’re there. And so sometimes you just might see a sign just sticking off the side of a building letting you know that’s part of the collection. Tonya (25:50) And the other part is the research. And there’s a lot of people who go there to research the history and culture of New Orleans. It’s really a gem. And speaking of gems, Judy’s photography in this book, Dancing in the Streets. It’s spectacular. Dear, I could only aspire to be as good as she is one day. The history is just incredible. The colors of the suits are vibrant. And I’m so glad that we were able to share this little bit of history with our audience. Ian (26:28) So it’s one of those things that makes New Orleans history and culture so interesting. Tonya (26:34) Absolutely. Ian (26:35) One of a kind. Tonya (26:35) Absolutely. In closing, let’s consider the words of Chris Rose, the Pulitzer Prize writer from The Times Picayune: “You can live in any city in America, but New Orleans is the only city that lives in you.” Tonya (26:55) We’re Tonya and Ian Fitzpatrick, and we’re so happy that you’re here. It’s our pleasure to feed your wanderlust and to share our beautiful human tapestry with you. Please support us with a five star rating and review on Apple Podcast or wherever you listen to podcasts. Ian (27:14) We’d love for you to join our community, so please subscribe to our bi-weekly newsletter from our website at worldfootprints.com. Our newsletter is full of travel news, tips and resources–including our favorite links. Tonya (27:29) Thank you so much for your support and for giving us the space to share the world through the stories we offer on World Footprints. Announcer 2 (27:38) This World Footprints podcast with Ian and Tonya Fitzpatrick is a production of World Footprints LLC, Silver Spring, Maryland. The multi award-winning podcast is available on worldfootprints.com and on audio platforms worldwide including iHeartRadio, Public Radio Exchange, iTunes and Stitcher. Connect with the world one story at a time with World Footprints. Visit worldfootprints.com to enjoy more podcasts and explore hundreds of articles from international travel writers and be sure to subscribe to the newsletter. World Footprints is a trademark of World Footprint LLC which retains all rights to the World Footprints portfolio including worldfootprints.com and this podcast.