Uncovering the Hidden History of a Free Black Brotherhood

Economy Hall is an important institution in New Orleans that speaks about hidden history of free black brotherhood. If author Fatima Shaik’s father had not rescued the records and books from early Economy Hall meetings that lay in a dumpster, we may not have known of the hidden history of free Black people in New Orleans.

Economy Hall was the meeting place for the Société d’Economie et d’Assistance Mutuelle (Mutual Aid). A benevolent society that was formed in the early 1800s by Louisiana Creoles and free people of color in response to oppressive whites’ efforts to diminish their rights and prosperity. The Economy Hall’s society brothers had a strong sense of community that endured through the era of slavery, the Civil War, Reconstruction, and Jim Crow terrorism. The brotherhood were activists, institutional builders and history makers who took care of their community.

In a story that is both personal and historical, Fatima takes us on a journey that begins with the rescue of the library of ledgers, journals and papers by her father in the 1950s. Further leading to the discovery that he had come to possess the documents that told the story of one of the most important institutions both for jazz and mutual aid for blacks in New Orleans—Economy Hall.

“Records and books from Economy Hall were in a dump truck until my father rescued them and put them in the closet where they lay for almost 50 years.”

Fatima Shaik

With records covering nearly a century starting in 1836, Fatima, while on a visit home to New Orleans in 1997—saw the journals sitting in a cabinet and decided to put them in chronological order on the dining table.

From that time on, Fatima would begin to construct a story that few of us had heard about. In her book, Economy Hall: The Hidden History of a Free Black Brotherhood, Fatima shines a light on the multiracial character of New Orleans, its Creole identity and a thriving Black community that shaped the social, political and economic character of a city and, by extension, the United States.

Join us as author Fatima Shaik uncovers the rich hidden history of a free Black brotherhood that was almost lost forever.

If you enjoyed this podcast please help others enjoy it too by providing a 5-star ranking, great review and subscribing on APPLE PODCASTS or wherever you’re listening to World Footprints. Your fellow travelers will thank you and we’ll be forever grateful!

FULL TRANSCRIPTS ARE IN LINK BELOW

Timestamps

[02:06] The Community Hall

[03:03] The Society Brothers

[03:27] The role of Economy Hall to the community of New Orleans

[04:24] Fatima’s personal story to the book: Economy Hall

[05:47] Who wrote The Society Brothers Journals?

[06:45] The business records of the journals

[07:27] The legacies of the journals

[12:36] The Black and White Creoles

[14:24] Fatima’s experience of growing in New Orleans during the Economy Hall

[16:43] Reader’s view of the New Orleans life

[17:31] Teachings from the Creoles Community and Black People

[18:41] The key takeaways from the journals

[19:53] What Fatima loves about New Orleans

Notable quotes

- “The goal of the Society Brothers was to take care of each other, educate each other, and help the suffering community.”

- “Many times when people look at black history, they see us as objects of history which is not the case. The men were activists of history. They took care of themselves and the community.”

- “The Society Brothers were an organization like Black Wall Street because they were so sufficient that they had business and cared for the community.”

- “Every time Black people get to a certain part of success, there would be some obstacles. However, the Economy Society was able to adapt and persevere throughout 400 years in the same neighborhood.”

- “Black people have to help each other and stay active. We don’t have to depend on anybody else. We have the resources to work with each other and help each other.”

- “Economy Hall does not exist today. It is actually a part of a community center school in New Orleans that has incorporated a playground. It is being used to serve the community.”

Resources

Economy Hall: The Hidden History of a Free Black Brotherhood

Fatima Shaik is the author of Economy Hall: The Hidden History of a Free, Black Brotherhood (The Historic New Orleans Collection, February 2021). She was born in the historic Seventh Ward of New Orleans and bred on the oral histories of Black Creoles told by her family and neighbors. Only after she read the records of the Economie—3,000 pages of handwritten French stored in her family’s home—did she realize this community’s impact. She spent two decades reading the journals and documenting events with real estate records, legal cases, old monographs, and articles. A former Assistant Professor at Saint Peter’s University and daily journalist, Shaik is a trustee of PEN America and member of The Writers Room in NYC. Economy Hallis her first work of nonfiction and her seventh book.

Book Your Stay in New Orleans, USA

Use the interactive map below to search, compare and book hotels & rentals at the best prices that are sourced from a variety of platforms including Booking.com, Hotels.com, Expedia, Vrbo and more. Search for ANY destination by clicking in the upper left corner of this map. You can also use the filter to fine tune your search, find restaurants, attractions and more!

Guests:

TRANSCRIPTION

Tonya Fitzpatrick 0:08

Thank you for joining us. I’m Tonya Fitzpatrick.

Ian Fitzpatrick 0:11

And I’m Ian Fitzpatrick, and this is World Footprints.

Fatima Shaik 0:17

I think the legacy is the activism that these people had. You know, many times when we look at black history or when people look at black history, they see us as objects of history. These men really were activists in history, they took care of themselves, they took care of their families, and took care of their friends, families.

Ian Fitzpatrick 0:40

That’s Fatima Shaik, Journalist, Historian, and Author of Economy Hall, the Hidden History of The Free Black Brotherhood, and a story that is both personal and historical. Fatima takes us on a journey that begins with the rescue of a library of luxurious journals and papers by her father in the 1950s to the discovery that he had come to possess the documents that told the story of one of the most important institutions, both for jazz and mutual aid for blacks in New Orleans. Economy Hall

Tonya Fitzpatrick 1:13

With records covering nearly a century starting in 1836, Fatima while on home to New Orleans in 1997, saw the journals sitting in a cabinet and decided to put them in chronological order on the dining room table. From that day, Fatuma would begin to construct a story that few of us have heard about, and she shined a light on the multiracial character of New Orleans. It’s Creole identity and a thriving black community that shaped the social, political, and economic character of that city and influence the United States at large.

Ian Fitzpatrick 1:51

Here’s our conversation with Fatima Shaikh

Tonya Fitzpatrick 1:56

Fatima Shaik. Thank you so much for joining world footprints today.

Fatima Shaik 2:00

Nice to be here. Thank you for inviting me.

Tonya Fitzpatrick 2:03

Tell us what is Economy Hall?

Fatima Shaik 2:07

Economy Hall was the meeting place of a group of free men of color. They built this place in 1857. It stood until the 1960s. In New Orleans

Tonya Fitzpatrick 2:18

It’s my understanding there were three at some point. Were they at three different locations or the same hall at three different times?

Fatima Shaik 2:28

When people talk about economy Hall, often they talk about the second location, which was a grand meeting hall and had a big theater. The three places that I talked about in the book are the first building that the Society Brothers purchased in 1836, across the street from the main one. And then they purchased the property next door. So they basically we’re on the same block in the same part of New Orleans for over 100 years.

Tonya Fitzpatrick 3:00

Who were the Society Brothers?

Fatima Shail 3:04

They started out as 15 Free Men of Color in the 1830s. But then they grew to encompass people from all over, all over New Orleans. Different parts of New Orleans. And then there were people who were in Mexico and France and Italy that are also Brothers of Economy.

Ian Fitzpatrick 3:24

Now, what was the role of Economy Hall and the men who were responsible for servicing New Orleans is community there. I know they provided things to serve funerals, and what we would call insurance could speak to that.

Fatima Shaik 3:45

It was a mutual aid organization, we would call it now a mutual aid organization. I think it was one of the most influential organizations of its kind, because they had people from all over, but they basically took care of each other, they joined together to educate each other and to help each other and to help suffering humanity. That was their goal. So, they did things for each other, and then they did things for the community.

Ian Fitzpatrick 4:09

Now you have a personal story to this book that you wrote, would you share that? Because it’s it’s really interesting, and I think it speaks volumes about why this book is so important on so many levels.

Fatima Shaik 4:25

Well, my personal story is that my father found these journals on the back of a dump truck, and they had been thrown out. The men of the economy had sort of outlived their usefulness by the mid-50s, that we had black insurance companies and we had funeral homes. So this sort of mutual aid society didn’t really have the same purpose that it had before. So people were joining younger organizations, so they decided to close up and get rid of the books. So they had tossed the books out and my dad rescued these books, put them in our closet, and said, well, one of these days I’ll get to it.

Tonya Fitzpatrick 5:01

Wow. But you got to it instead.

Unknown Speaker 5:06

Yeah. And when I opened them, I found these men who had been so influential in New Orleans and had really been written out of history. You know, it was, it was really surprising to me how much I found about them after I knew their names, because the journals themselves, now this was 3000 pages of French and writing, okay, their journals told a lot about where they were at any particular time. But then I used secondary sources to just look through the books to see was this name mentioned was that I mentioned. And I found that they had been very active in New Orleans, in many things,

Tonya Fitzpatrick 5:42

Who kept these journals who wrote in these journals?

Fatima Shaik 5:46

The society themselves kept the journals. These were the minutes of their meetings, and their meetings went anytime from once a week to once a month. But the society Secretary kept the journals, and the society Secretary that I follow is a man named Ludger Boguille. They would probably say it differently in French, but a notable Boguille family in New Orleans say Boguille.

So, Ludger was one of the most prolific secretaries. He wrote in this beautiful script. And he just put in all sorts of asides, you know, like he would put exclamation points if somebody was really angry at a meeting, or he put underlines, you know, so it made me feel his passion for the organization and for what was going on.

Ian Fitzpatrick 6:32

These journals that you speak of that are minute meetings. Were they also business records, and what were you able to glean from them in terms of the business side?

Fatima Shaik 6:48

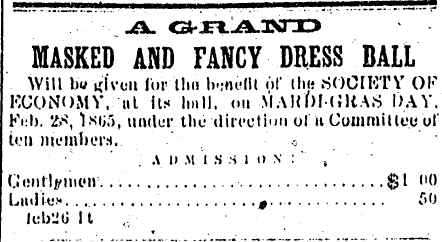

On the business side, I found out how much money they were giving to people. One of their first balls, they gave a ball to the nuns, the Sisters of Charity, and they collected something like $369, this was in 1841. So that was quite a bit to collect in one night. And they gave that money to the nuns. So, I would see these sorts of records. How much they were giving to people, how much a funeral cost, and how much insurance they had purchased on the building—those sort of things.

Tonya Fitzpatrick 7:21

What are some of the legacies that you reference in your book, the legacies of these journals?

Fatima Shaik 7:29

I think the legacy is the activism that these people had. You know, many times when we look at Black history, or when when people look at Black History, they see us as objects of history. And these men really were activists in history, they took care of themselves, they took care of their families, they took care of their friends, families. They built institutions, you know, so you see how they were active not only in their community, but they were active in the suffrage movement. Ludger Boguille spoke at the first color convention in Louisiana, and he’d spoken French. So who knew that the convention went on in English and French? So you see these sorts of things that they’re doing? They’re very active, they’re not objects at all. They’re actors in American history.

Ian Fitzpatrick 8:16

One of the things about New Orleans because it’s a strongly Catholic places that there’s so much written history available to kind of go back to the past. This seems to continue with that legacy. So were these records unique for Creole and African American people? Or was this just kind of standard operating procedure for a lot of organizations?

Fatima Shaik 8:45

Well, I’m not quite sure if it was standard operating procedure, I haven’t found anything else. So, there was, for example, an organization called The Young Friends. And there were lots of these sorts of organizations. The Economy was one of the first however, that was Black men doing it for themselves. There were few Catholic organizations, and there was one, this was a group of poets who also had an organization around the time of the economy. No one’s ever found their notes.

So if they did take notes, we don’t have them. And I tend to think that The Economy was a special in a way, because these men had a lot of money, and they had a lot of education. So even though you got organizations later on after the Civil War, because there was a real push for self-help, after the Civil War. You didn’t see people who had this level of education and this level of flexibility. They really traveled, they traveled to Paris all the time, you know, individual members, and they traveled to Mexico. I don’t think everybody was writing about that.

Tonya Fitzpatrick 9:57

It almost sounds like, The Economy Hall, always precursor to Greenwood and you know Tulsa, the the Black Wall Street.

Fatima Shaik 10:07

Oh, right. Yeah. There were one statistic that I found that I’ve only seen New Orleans history separated into Whites free People of Color, and Inslaved. Then when I when I put together when I said, Okay, what was the real population numbers at the very beginning there were Whites and two thirds were Enslaved people and free People of Color. So really the Whites were out numbered. Another thing that I found out was that among the blacks in New Orleans, just about 45% of the population was free, which is, which is a statistic you don’t find in other places in the United States.

They have been free for about four, four decades before the Civil War, about half of the population. So that compares to about 14% of the rest of the United States before a civil war. So to back to your point about Greenwood. Yes, they were organization that was like Black Wall Street because they were self sufficient. They had businesses, they took care of their community. But there was a lot of wasn’t just a little, you know, there were a lot of people doing

Announcer 11:18

This is the award-winning World Footprints Podcast with Ian and Tanya Fitzpatrick. World Footprints connects you to the world through powerful storytelling that uncovers the full narrative of our cultural and human experiences. Discover the world when you visit our website, world footprints.com. And make sure you sign up for our newsletter to receive exclusive content.

Tonya Fitzpatrick 11:41

Here’s more of our conversation with Fatima Shaik, Journalist, Historian, and Author of Economy Hall, the Hidden History Of a Free Black Brotherhood.

You talked about the different segments of the population and I know within even the Creole group, there are White Creoles and Black Creoles. But talk a little bit about that and how they define themselves.

Fatima Shaik 12:14

I think if you ask every Creole, you’ll get a different answer. That’s number one. Let’s start there. In my tradition, it’s been called people born during the colonial period, from someone who came from outside of Louisiana, another nation, or another continent, and their children were born in Louisiana and their descendants. So people born before the United States started in Louisiana.

The idea of people being Black and White Creoles came on a little later because, at the very beginning, it was, are you enslaved? Are you free? So the free people include the free people of color and the whites. Now, ask anybody in New Orleans talking on the corner about Creole. They’ll tell you that when the Americans came, things changed because when Louisiana was put in American governor, the fact that you were free and colored had to go on every document.

Before, if you were a free person, you just signed your name. When the Americans came in, it was free color. It made a difference. So every document now has your race as well as your status. That became virulent, after the Civil War, because of White Supremacy. After the Civil War, there was that push. There was a time of reconstruction. We had that good ten years, 12 years, and reconstruction. But after Reconstruction, White Supremacy became virulent. So people made a real distinction between whether you are White Creole or Black Creole, it became crucial.

Ian Fitzpatrick 14:06

Now, your book tells the story of The Seventh Ward in New Orleans where Economy Hall was situated. What can you tell us about life then and share some insights as to what was it like for you growing up there?

Fatima Shaik 14:26

Well, the Economy Hall was in the Sixth Ward, which is adjacent to the seventh floor. But what happened was the people from the sixth Ward moved into the seventh floor, they were starting off around the French Quarter, and they moved a little bit further and further toward the lake. So, in that time, in the sixth Ward around Economy Hall, there were a lot of businesses, there were a lot of businesses that were owned by black people, construction companies, shoemakers, you know, all sorts of people. By the time I was growing up, it was their second-time Third generation.

So you have people who had maybe education, but two or three generations move there that came with businesses, we had an area, right on the edge, sort of between the seventh Ward and the sixth Ward called Claiborne Avenue in on Cleveland Avenue where black doctors, black businessmen, stores, shoe stores, anything that you could want, you could go to Cleveland Avenue and find it. What happened was the interstate highway came in, in the 60s and just ripped up that whole successful area, which had really been going on for two or three generations.

Tonya Fitzpatrick 15:38

When you were going through these journals, Did you, by chance, uncover any of your own family history?

Fatima Shaik 15:45

Well, no. I found my family history subsequent to that, you know, I started doing genealogy and stuff. But I found all my neighbors, the people who lived across the street from me and the same people in The Economy Hall. All the people that lived around the corner had the same name as the people in Economy Hall. So, I went to grammar school with these people, you know, we talk about their families owned businesses, and their families had this and we were living in segregation at the time, right? We don’t believe that you just tried to make yourself into something you’re not. But that was it.

Ian Fitzpatrick 16:24

Now, your book has over 500 pages, pictures as well. What are you hoping that the readers will experience as they go through this really deep dive and in depth view of this slice of New Orleans life?

Fatima Shaik 16:44

Well, I tried to make it personal, I want them to see people like Ludger Boguille as real people. First of all, I want them to realize that real people were active in American history. And that every time, well for Black people, every time, we would get to a certain part of success, there would be some obstacle put it in our way. What’s really special about the economy society is that they were able to sort of adapt and persevere throughout 400 years, in the same place, in that same neighborhood.

Ian Fitzpatrick 17:18

Now, it’s often said that history is a fight about the future, what do you think the reader can glean from the experience of, of the Creo community and black people, enslaved people, from looking at this book to help us as you we’re dealing with some really turbulent times today?

Fatima Shaik 17:41

I think what people can learn is that for one, we need to stick together, that you saw from the economy men when Enslaved people became free, they were helping them get suffrage, they were teaching. So one opportunity that we have is to help each other. Another one is that we have to stay active. It’s not that we can get to a certain place, and then just decide, okay, well, we’re not interested in Black History, we’re not interested in our neighbors anymore. We have to be active in our communities. So I think that’s something that we can take into it. And, we don’t have to depend on anybody else. We have the resources, to work with each other, and to help each other.

Tonya Fitzpatrick 18:24

As you were going through the journals, is there a story that really surprised you, maybe you knew a little bit about it, or a new story that really resonated with you? What did you take away when you went through those journals?

Fatima Shaik 18:41

As a writer, I took away their literacy, it was just really amazing to me that they had a library in 1836. At a time when enslaved people could not read or write, were not allowed to learn to read and write. And at a time when free People of Color were told not to think of themselves as equals. Which is just kind of amazing. Don’t even in your mind, think about that. You have equality. These guys, you know that they just ignored these laws. They just ignored it. They put the librarian ahead. I found these beautiful atlases, you know, there was a gorgeous Atlas there. They had books about PTO and Haiti. They had books about the government of France, the fact that these people had a library, they had set it up to educate themselves. So it took for me the idea that they were so literate, and they wrote so much that really resonated with me.

Tonya Fitzpatrick 19:34

Before we go, I want to ask you about New Orleans because anyone who follows us knows that New Orleans is our second home. As somebody who grew up there. What do you love about New Orleans and where do you go when you go back home because you’re not living there right now.

Fatima Shaik 19:52

I’m not living there. And the only reason I’m not there right now is because of the pandemic. I’d be spending, you know, four wants to New Orleans easily. What I love about it the most is the community. I don’t think I have any special place you know, that means so much I love the lake for me. I like to wander around in the French Quarter and get Benny’s, you know, but what I like is the community, the fact that I can come out of my house and people want to talk, you know, they want to talk about how are you? You know, I remember your mama. I was sitting on my porch one day, a guy came by and looked a little sketchy. And he kept saying, Hey, okay, so let me talk to this. So I started talking to him.

He said your mama taught me in first grade. It was wonderful. He just he just said things like, my mother was so nice to me and look at how well you’re doing. You know, I mean, it’s that kind of reinforcement that you get in New Orleans, that people appreciate you and you appreciate them. So you this can happen on your block, this can happen at the grocery store. This happens all the time, you know that you really have a love for the people that you grew up with and even strangers.

Tonya Fitzpatrick 21:15

There are so many things that really struck me during our conversation with Fatima. But I think what really resonated with me was the fact that they were free black men in the early 1800s. And that’s something we didn’t know about, we don’t hear about. And what it showed was the power of community back then.

Ian Fitzpatrick 21:35

And these were worldly men. They were well educated, they had money. And they were influential, and being literate, as Fatima mentioned during the interview gave them an opening and a point of view that very few People of Color black people had at that time in history. And so that was really revelatory about learning of Economy Hall

Tonya Fitzpatrick 22:04

The thing that her father saved those journals. They were in a dumpster ready to be tossed. Those are stories we would have lost but for Fatima’s dad and me for one, I am very grateful. I wanted to tell our listeners that you actually did a little bit of background on Economy Hall itself, the building, what did you find?

Ian Fitzpatrick 22:27

What I discovered is that Economy Hall does not exist today. It is actually part of a community center school in New Orleans that has incorporated where Economy Hall one stood into a play area, a playground for the school and the community. So it’s being used to serve the community but in a different way.

Tonya Fitzpatrick 22:51

It’s a pity that the building was lost. In closing, we’d like to leave you with these words from Ellis Marsalis, the late jazz pianist, musical educator and native son of New Orleans who gave us a musical dynasty primarily through his sons. And he’s someone whom we had the pleasure of interviewing many years ago. What a blessing he was. in New Orleans culture doesn’t come down from on high. It bubbles up from the streets. Oh, my is he ever so right about that?

Ian Fitzpatrick 23:26

I guess that’s how New Orleans gets up in you

Tonya Fitzpatrick 23:29

As James Carville told us. We’re Tanya and Ian Fitzpatrick and we are so honored that you spent this time with us. Thank you for allowing us to connect you to the world through the stories we share on World Footprints.

Auto 23:46

This World Footprints Podcast with Ian and Tonya Fitzpatrick is a production of World Footprints LLC Silver Spring, Maryland. The multi-award-winning podcast is available on worldfootprints.com, and on audio platforms worldwide, including I Heart Radio, public radio exchange, iTunes, and Stitcher. Connect with the world one story at a time with World Footprints. Visit worldfootprints.com To enjoy more podcasts and explore hundreds of articles from international travel writers. And be sure to subscribe to the newsletter, World Footprints is a trademark of world Footprints LLC which retains all the rights to the world footprints portfolio, including worldfootprints.com and this podcast.