God’s Little Acre: America’s Colonial African Cemetery preserving history in stone – Part 1

Have you ever heard of God’s Little Acre? Today you are in for a treat! In this episode of the World Footprints podcast, we have the privilege of interviewing Keith Stokes, advisor to the Rhode Island Black Heritage Society.

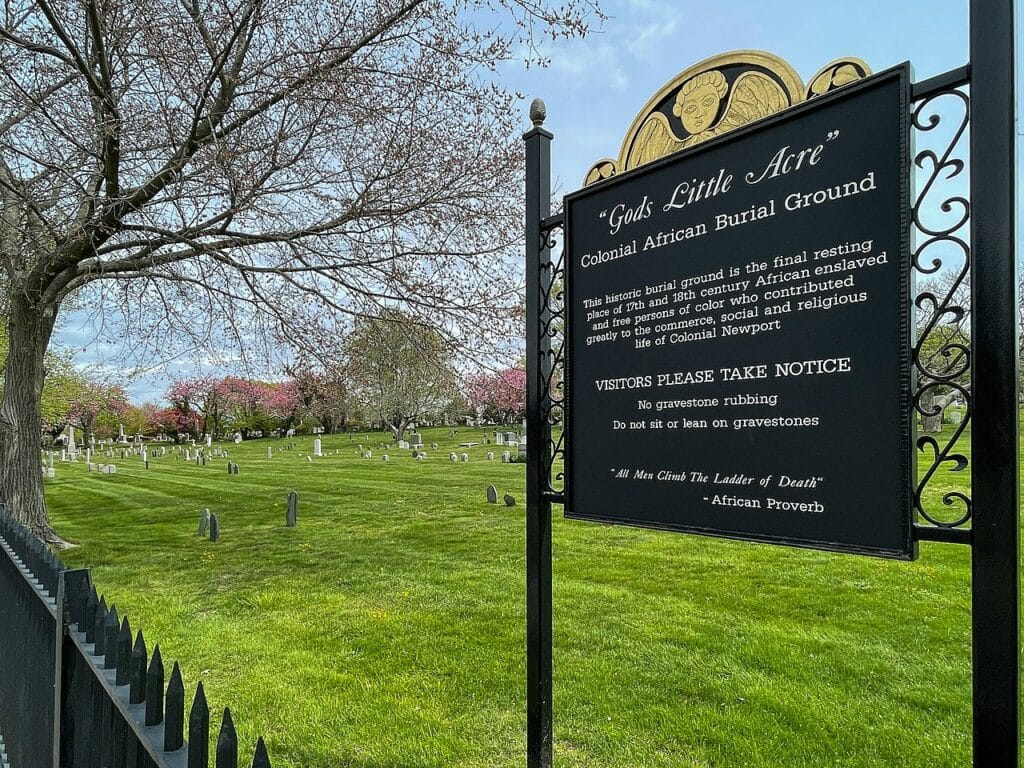

We met Keith in Newport, Rhode Island in a section of Newport’s Common Burial Ground known as “God’s Little Acre”—recognized as the oldest and largest colonial African burial grounds in the United States. Dating from the late 1600s, “God’s Little Acre” holds the graves of over 300 enslaved and free Africans and provides insights into their lives through the commemorative images and words etched into stone markers.

Keith takes us on a walk around the cemetery and keeps us captivated by the many underrepresented stories revealed by the stone markers.

“Slavery is how we got here. It tells you a little about who we are as a people.”

–Keith Stokes

This episode represents Part 1 of a two-part series.

What You’ll Hear in this Episode:

[04:59] The Common Burying Ground

[07:12] The beginnings of a benevolent society in Newport

[11:08] Newport’s connection to the slave trade

[13:58] God’s Little Acre is not the story of slavery

[15:40] “History is about power”

[17:44] Difference between markers of the enslaved and markers of free Africans

[20:00] Who is Pompey Brenton?

[21:18] Slavery in New England

[24:27] Meaning behind the colonial names given enslaved Africans

[26:04] Previewing Part 2 of God’s Little Acre podcast

Notable Quotes:

“The common burying ground represents possibly the earliest successful experiment of racial class integration in the Americans.”

“Slavery is not black history. Black history is how our ancestors survive and thrive despite slavery or what my grandmother told me as a boy. Slavery is how we got here.”

“This bearing ground here represents a testament of the survivability of African heritage people who arrived despite the worst circumstances put a place upon them.”

“History is about power. White folks, white institutions use history to justify the power that they either have, or they’re willing to seize and have. We need to use our black history as a sense of entitlement, power, and identity.”

Connect with the world one story at a time with World Footprints. Visit worldfootprints.com to enjoy more podcasts and explore hundreds of articles from international travel writers. And be sure to subscribe to the newsletter.

Book NOW to Stay in Newport

Use the interactive map below to search, compare and book hotels & rentals at the best prices that are sourced from a variety of platforms including Booking.com, Hotels.com, Expedia, Vrbo and more. You can move the map to search for accommodations in other areas and also use the filter to find restaurants, purchase tickets for tours and attractions and locate points of interest!

PODCAST & FULL TRANSCRIPTS BELOW

COVER: God’s Little Acre, the colonial African burial ground in Newport Rhode Island. Photo by Kenneth C. Zirkel CC 4.0

Guests:

[00:00:10.010] – Keith

The Africans talked about that here at the time. They actually talked about returning to Africa 30 years before the American colonization movement, which was organized by white folks to basically remove free Negroes who had influenced enslaved Africans. Whereas here Africans who were African born or one generation mover saying, no, it’s time for us to return to our country. And they organized it and you’ll meet some of the markers of people, family members who remain, but others had left. So, it’s again, the story of God’s Little Acre is a story of survival. It’s a story of identity, the story of power. And I have to emphasize again, they saw themselves as Africans. The first institutions in America are called African churches, African benevolent societies, African schools. They’re African. It’s only later that we become colored and Negro and black and that’s just distance ourselves from our original African identities.

[00:01:07.830] – Tonya

Welcome. This is World Footprints. And I’m Tonya Fitzpatrick.

[00:01:12.690] – Ian

And I’m Ian Fitzpatrick. You’ve just heard a clip from our interview with Keith Stokes, advisor to the Rhode Island Black Heritage Society.

[00:01:21.690] – Tonya

We met Keith in Newport, Rhode Island on the grounds of God’s Little Acre, a colonial African cemetery that is situated within the ten plus acre boundaries of common burying ground. Newport’s oldest public cemetery, God’s Little Acre dates back to the late 1600s and contains the graves of over 300 enslaved and free Africans.

[00:01:46.940] – Ian

God’s Little Acre has been recognized as the oldest and largest colonial African burial ground in the United States. With over 300 stone markers, the burial ground offers an abundance of clues to Newport’s cultural heritage. And as we walk the burial grounds, Keith captivated us with many underrepresented stories revealed by the stone markers.

[00:02:10.370] – Tonya

Keith made clear that these stories are not about slavery or the slave trade. Rather, they are stories that reflect the rich cultural tapestry of Newport and a new way of telling an old story of how Africans arrived and persevered in early America. In the first of this two part series, you’ll be introduced to early Newport culture and renowned citizens of African heritage.

[00:02:37.970] – Keith

Just to give you some context, what we today call God’s Little Acre or the African Burying Ground, Negro Burying Ground is this section. That’s my car there. So, this entire nearly two acre section is God’s Little Acre and it contains about 300 markers from the 17th [century] to, well, my parents. But today it’s recognized as the oldest existing continuous use African burying ground in America. There would have been others that are larger, certainly New York, Boston, Philadelphia but unfortunately, they were deconstructed through urban redevelopment and riots and acts of God whereas here things were preserved. So, every slate marker that you see is an African heritage person. Most of the marble are later African heritage people.

[00:03:26.100] – Ian

As a backdrop, Keith tells us…

[00:03:29.330] – Keith

The founding of New England, which we today call American irony, was based upon religious freedom and toleration. If you were a Protestant Christian so by the mid-17th century, Newport became a magnet for most of the Old World persecuted religious groups. The first Quaker community in Americas is not Philadelphia at Pennsylvania. It’s here. And we have the oldest existing Quaker meeting house here, and that’s 1657. They’re arriving and establishing themselves. A year later, Sephardic Jews arrive, and this becomes, along with New York, the first and largest Jewish settlements. And as they’re all arriving, they can be tolerated based on their religion, but they bring with them their worldwide connections. Many of the Sephardic Jews came from Spain and Portugal, who are already deeply involved in the slave trade. So, they brought with them Spanish connections to the Old World, to the Caribbean. They brought technologies. I mean, we have enslaved Africans that you’ll see in Jewish households that not only take on Jewish identities, they’re leading their craft skills. They’re making Castilian soap, rum making, chocolate grinding. So, what’s important to understand is that the irony is that we’re establishing the tenets of religious freedom and toleration. Those same families who are persecuted religiously almost immediately enter the transatlantic slave trade without batting an eye.

[00:04:45.470] – Tonya

We found it curious that the burial grounds for enslaved and free Africans and African Americans were not separated from the larger common cemetery. So, Keith provided some historical perspective.

[00:04:59.090] – Keith

It’s a little over ten and a half acres in total, which is called the common burying ground. The common burying ground was established in 1640 by, at the time, Reverend John Clark. Reverend John Clark today is recognized, along with Roger Williams in Providence and Anne Hutchinson in Portsmouth, as the three leading European founders of what is the colony of Rhode Island. John Clark actually, in 1663, travels to England and negotiates and brings back the charter that organizes the colony of Rhode Island under the British Crown. John Clark also is with Roger Williams, the first to express a separation of church and state. He felt passionately to the fact that this colony should be ruled by a democratic system. And it wouldn’t be a royal governor based on a religious background. It certainly wouldn’t be any type of religious requirements. So, John Clark deeded this land in the northern part of the town at the time for the purposes of a common burying ground, not cemetery. That doesn’t come into vernacular until the really midpoint of the 19th century. So as a common burying ground, as a part of his deed of trust to the town, anyone could be buried here, regardless of religious background or class.

[00:06:11.270] – Keith

So you have a number of colonial governors here–our signers of the Declaration of Independence. You have enslaved and free African people all living in this. In fact, this burying ground represents possibly the earliest successful experiment of racial class integration in the Americas. It’s a living testament to that. By 1705, this section that we stand in begins to have the termination of being a Negro burying ground, as they called us at the time, both enslaved and free by the mid-19th century, the Free African Heritage Church, the Union Colored Congregational Church. My ancestor, who was the minister there from 1868 to 1897, they began to use the biblical terms and call it God’s Little Acre. But in any case, today God’s Little Acre section of the common burying ground has the largest and oldest existing number of burial markers of African heritage men, women, and children dating back to, again, the 17th century. So, what’s exciting about this place today for us is you actually get to see markers that not only provide an interpretation of what slave life was like for African heritage people, but later, by 1780, many of the free Africans now in Newport form the first free African benevolent society in America.

[00:07:31.390] – Keith

And five years later, they interact with their counterparts in Philadelphia, Boston, Providence, and Newport. And by 1790, those four communities have active free African benevolent societies. In Boston. It’s led by a man named Prince Hall. In Philadelphia. It’s led by Richard Allen. What’s important is that these are what we call our African founders of America. They not only found the societies, every one of those societies that evolved into a free Black church.

[00:07:58.750] – Tonya

I asked Keith if there was a connection with a benevolent society in New Orleans. We did a podcast on last year. I was very surprised to hear that New Orleans came later.

[00:08:09.600] – Keith

We’re talking about 17 [th century]. We’re talking about at the time of the American Revolution. Immediately after, in many times in those locations. They’re not even a part of the United States of America yet there’s not a United States of America at that time. So, it’s important to recognize that. Let me just step back how this became an African burying ground. We are part of British and North America in the 17th and 18th centuries, and Rhode Island as a colony is one of the earlier colonies of the British Crown. Rhode island at that time becomes being a seafaring state, being an ocean state, Rhode Island becomes the most active and most productive seafaring colony in the British crown. By 1750, Rhode Island is the third largest seaport behind New York and Philadelphia. Newport, Boston, and Charleston–those are the leading seaports in the British Crown. But here in Rhode Island, unlike, say, Charleston, South Carolina, Richmond, Virginia and elsewhere, it’s New England land and weather. We have bad soil and inclement weather. So the economies that we’re tied to in our maritime trade are not based upon the cash crops. We’re not growing tobacco or cotton or sugar.

[00:09:15.790] – Keith

Any of that–coffee–is happening here. So what we find our merchants deciding to do is to get into the craft trades or the aptomotic trades. They would take commodities and cash crops such as sugar and make it into chocolate. They would take sugar and molasses and make it into rum. By 1760, Rhode Island here at Newport, we’re the largest guinea rum distillers in the world. We had 24 rum distillers. So, our connection to the African slave trade is tied to the fact that Africans would be the labor force of the West Indian plantations and later southern plantations. Rhode island merchants become the feeder of that enslaved labor force. So, between 17 five and 18 five, we now have as primary documentation. Rhode island was involved in at least 938 slave voyages to what we call the triangular trade, leading Rhode Island, largely Newport, almost all Newport, to the Gold Coast, what is today Ghana. Because again, you have to understand that we’re a part of the British Crown, British colonies. So, along the West African coast, what is today Sierra Leone, northern Nigeria, Ghana are very specific and very consistent English African slave trading locations in the West Indies, it’s Barbados and Jamaica.

[00:10:30.970] – Male Announcer

You are listening to the award-winning World Footprints podcast with Ian and Tonya Fitzpatrick. World Footprints connects you to the world through powerful storytelling that illuminates our common humanity and uncovers the full narrative of our cultural and human experiences. Support World Footprints by leaving a five-star rating and review on Apple podcasts or your favorite podcast platform. This will help other like-minded and interested travelers find us. Also, please join the World Footprints community by subscribing to our newsletter from worldfootprints.com.

[00:11:05.190] – Tonya

Here’s more of our conversation with Keith Stokes as we continue our walk-through God’s Little Acre.

[00:11:12.390] – Ian

Many people would be surprised at New England’s connection to the slave trade in terms of its involvement and the depth we often think about the southern ports, the southern United States. But I know from my own research there is a family, the DeWolf family, that was very active, perhaps one of the leading, if not the…

[00:11:38.760] – Keith

That gets embellished. I mean, let me be candid. My kids are 9th generation Newporters. My ancestors were part of the earliest and enslaved Africans arrived. We own slave artifacts. They’re buried here. My immediate family is buried here. African heritage in history many times still continues to be interpreted from a white owner class perspective. And even though there’s all the good intentions, it’s still based upon the white institution. Let me be clear. Slavery is not black history. Black history is how our ancestors survive and thrive despite slavery, or what my grandmother would tell me as a boy. Slavery is how we got here, but it tells you little to who we are as a people. The DeWolf families were part of a large group of prominent white families across New England who actively participated and dominated within the transatlantic slave and slave owning. But in the case of Rhode Island, it is Newport. 76% of the boats that sailed from Rhode Island to West Africa into the West Indies and back to Rhode Island came from Newport. So, DeWolf’s were certainly a participant and a significant participant, but nowhere near the level of the Rhode Island merchants and the Newport merchants.

[00:12:47.660] – Keith

So, I just get very cautious of the fact that we’re still focusing on the legacies of slavery in the institution when we should be focusing on the legacies of how people that look like us survived it, thrived it, and would later establish what is today nearly all of our major African heritage institutions. And what’s interesting is having the opportunity and privilege to travel across the diaspora and lecture and work with African heritage historians in the West Indies, in the west Africa, they take an African central perspective. Here in America, we’re still looking at through the lens of the slave master or the descendants of the slave master. We need to interpret this history from the eyes and lens of the Africans themselves. And we can do that because being old in New England, we have lots of old stuff, lots of old documents, diaries, artifacts, and it includes lots of old African and later African American documents and diaries. So, this burying ground here represents a testament of the survivability of African heritage people who arrived despite the worst circumstances, put a placed upon them.

[00:13:52.330] – Tonya

Keith reminded us that God’s Little Acre is not the story of slavery.

[00:13:58.110] – Keith

In 1787, the free African society in Newport established their own African burying society and fund. They had rules and regulations. They had in fact, today, we sometimes, and we’re in New Orleans, recognize it as the jazz funeral, where it could be junk anew in the Bahamas. But right here in Newport, across of the diaspora in the 18th century, there were African funerals that followed, very specifically the Akan people of today’s Ghana ceremonies. We have hundreds of Africans assembling in the center of town marching here, chanting, drums, music to lay the rest of their dearly departed, because under the Akan tradition, they’re being reunited with their ancestors. And then after there’s a celebration, white folks went out of their minds hearing this and seeing this. They didn’t understand it. See, that’s the challenge, starting at the time that we arrived here through the Americas, our culture, our language, our very identities is being interpreted from a white lens, and it’s still going on today. In fact, the booklet that I gave you that my ancestor [Rev. Mahlon Van Horne] wrote in 1886, he was the first black state representative in Rhode Island, 1885, and he’s buried here at Island Cemetery. He wrote that piece called the Future of the Negro in Rhode Island–Past, Present, Future.

[00:15:09.380] – Keith

But read what he says, because what he’s talking about in there in 1887, that’s a Black man talking about his experience as a man of the cloth, an activist, a friend of [Frederick] Douglas, talking about what life was like past, present, and future and what the expectations of our life would be. You read his words, then it aligns very closely to the Black Lives Matter Movement and the words that we hear from young people of color today. And my job, my interest, my passion is getting these words this history in the hands and in front of kids of color. Let me be clear. History is about power. White folks, white institutions, use history to justify the power that either have or they’re willing to seize and have. We need to use our black history as a sense of entitlement power, identity. Every African heritage kid in this community, I tell them, you have as much a right to succeed here because you were here and your ancestors well before most others. And they struggled and they survived and persevered. So, I see history as identity building and power building. White folks see it as reconciliation…

[00:16:17.340] – Tonya

Or as Critical Race [Theory] whatever Critical Race [Theory] is there. I have no idea what that means.

[00:16:20.440] – Keith

The bottom line is that white folks and institutions see all of this as a part of their diversity and inclusion and equity. We don’t care about diversity and inclusion. We want equity. Give us an equal standing, an equal financial capability, and then we’ll choose where we live, work, or worship it. I mean, one of them. And we’ll walk and see markers. The Africans talked about that here at the time. They actually talked about returning to Africa 30 years before the American colonization movement, which was organized by white folks to basically remove free Negroes who had influenced enslaved Africans. Whereas here, Africans who were African born or one generation mover saying, no, it’s time for us to return to our country. And they organized it. And you’ll meet some of the markers of people, family members who remain, but others had left. So, again, the story of God’s Little Acre is a story of survival. It’s a story of identity, the story of power. And I have to emphasize, again, they saw themselves as Africans. The first institutions in America are called African churches, African benevolent societies, African schools. They’re African. It’s only later that we become colored and Negro and Black, and that’s just distance ourselves from our original African identities.

[00:17:34.920] – Keith

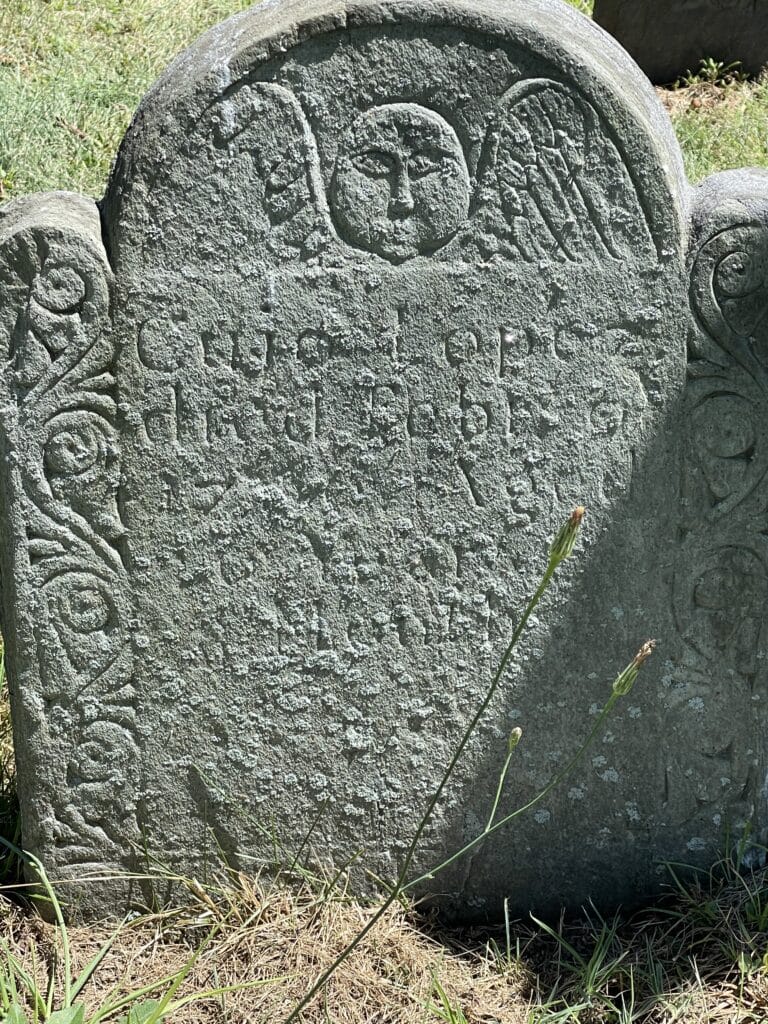

Just to give a sense, look at some of the markers. You’ll see a distinct difference between markers of the enslaved versus markers of free Africans. But one of the things that you’ll see, which is an important touchstone here, you notice this is Cujo Lopez. This is his headstone. footstone, 1769. Cujo is the phonetically interpretation of Kojo. As I said earlier, most of Rhode Island ships were landing in British held slave fortresses in the Gold Coast, which is today Ghana. So, Cape Coast, Castle, Fort William, Anomabu my own ancestor came from Fort William to Jamaica and then became at eight years old, he became a Windsor chairmaker and a tradesman. So, what’s important to understand is that as we see these markers here, you’ll see lots of evidence of Akan traditional day names. Cuffy or Cuff is actually Kofi. Kofi boys born on Friday. Cujo is Kojo, Kojo boys born on Monday. One of the things that Africans were able to do here is either they retained or after slavery, they retained their African identities and names and passed it on to their kids. My ancestor name was Otoba, which became October. Otoba means to stay put.

[00:19:04.290] – Keith

Again, they’re all a part of the Akan Fante people of what is today Ghana. So, as we look at these markers, there’s so much more here than just simply what whites have done. A slave marker, a slave name, an unusual name because they didn’t have a passion or interest or connectivity than the fact that we had culture, we had tradition, we had religion well before Europeans set foot on the African continent. And then, just to give you a sense, we’ll, look, I’m going into my third knee surgery. So that’s why it’s been tough walking around. So, all of these, again, are Africans, all of the slate markers, and we’ve been spending years and money restoring them one by one. It cost us about $25 to $3,000 per marker to restore by hand. This is probably one of our more photographed markers because of its imagery. Pompey Brenton is a free African. He is a clerk in the household of Jahleel and William Brenton, who are the royal governors of Rhode Island. Some of the founders, they would introduce trading in 17th century Barbados. But what’s important about this marker is that what we call sometimes the death head are the image in Christianity of life after death.

[00:20:32.590] – Keith

So, it’s an image that usually has wings or an angel and such. But you will see several markers here where the actual imagery has African features. There is nowhere where you see enslaved and free Africans. In the early time of America, not only United States, but the Caribbean, will you see an imagery that provides an African identity, and again, that gives you a sense of them recognizing who they were and the larger white community recognizing who they were. There’s three very important points to understand of slavery in New England generally, particularly in Rhode Island, because we we tend to sometimes see slavery through the lens of the antebellum south, obviously, because that’s been published more and commercially, covered more and roots and such. But the reality is that slavery in the Americas, particularly British North America, started here in New England, the earliest colonies. So, when the Africans arrived here, there’s no cash crop, agricultural based economies. There’s nobody working in plantations and farms. Those that are working in plantation farms are very small. And it’s animal husbandry, it’s sheep raising, it’s horse raising. That’s what my ancestor did. But in the urban seaports, like Boston, London, Philadelphia, ports of New Hampshire, Bridgeport, Connecticut, Newport, they’re all being trained in the trade skills because that’s what was demanded at that time.

[00:21:54.120] – Keith

So, unlike the south and certainly the Caribbean, access to training and access to education was a priority that would have been unheard of, unnecessary and unlawful. So, most of the Africans that arrived here, surviving the Middle Passage from west Africa to West Indies. And eventually here were children under the age of twelve because you have to understand that to apprentice in a skill, it took five to six years to be a master carpenter, shipwright women in seamsters and sail lofts. So, for the most part, they’re brought here young as a valuable commodity. And then they spend the next four or five years learning that trade. As I said, my ancestor came from what is today Ghana to Jamaica to Philadelphia to Newport, and he’s trained as a Windsor chair maker and a finished painter. So, by the time these Africans became free, they had language skills, they had trade skills even far beyond whites, and particularly the arriving whites from Ireland and Scott-Irish and Germans arriving, they were the most literate. So, it’s important to understand that men like Pompey Brenton, who is a clerk for the governor we have a number here also represented one of the earliest Africans in one of the earliest African customs.

[00:23:00.790] – Keith

Here we’ll walk back in the shade here. It starts almost simultaneously in Newport, Providence, Warwick, Boston, New Bedford, Hartford. We even see it starting in Kingston, Jamaica, anywhere there are large concentrations of enslaved Africans who originate as the Akan people. They begin in June having a celebration where they come together and they select a tribal chief. And then they have a series of recognitions of weather and recognition of their culture and identity. The white community called it Negro Election Day because they thought they were mimicking European elections, selecting a Negro governor, when in fact it’s the Akan Yam Festival. And again, you have to go across the diaspora and back to Africa to see the festival, see them, and you understand that’s what they were doing. Pompey Brenton is one of a number of Africans who’s elected as an African chief in one of those festivals. And in Newport, it’s quite interesting, the diaries that we have. Every African enslaved and free to vote had to have at least an ownership of one pig. So it gives you a sense of ownership both enslaved and free.

[00:24:11.010] – Tonya

I wanted to ask you about the name Pompey because it seemed to be a very common name spelled differently. But there’s also a story here about one Pompey or one Kofi teaching another Pompey about the art of masonry.

[00:24:28.130] – Keith

We’ll clarify that there’s names like Caesar and Prince and Queen and Pompey and such and Cato. The elite Europeans at that time, our ancestors were possessions, could have been a horse, could have been a pig or a cow. And enslaved African were a possession. And out of that pride of having so many of those possessions who were so well trained and great servants, they would give them names from the Greek classics, from the Roman. It was almost this way of saying, my enslaved African woman is a queen, mine is Pompey and such. In fact, many of the Africans in Newport, particularly once they become free, drop all that craziness and take back their African names. Many would convert into the household of their master mistress. So many become Christians, so they take on Christian. And you’ll see here a little boy named Solomon Nuba Tikey, and his father’s name is Arthur Flag, but his father’s name was Nuba Tikey, but he converted and kept his name Arthur Flag, but he would name his son his African true name. So, again, this is all what we call today in Rhode Island creative survival. Even today, we’re always trying to think of ways of just getting ahead, surviving, maintaining our dignity and identity.

[00:25:41.720] – Keith

And that’s what these Africans were doing. And you see it all within these markers in this burial ground.

[00:25:48.190] – Tonya

This is just the beginning of our conversation with Keith Stokes, and there’s already so much to reflect on.

[00:25:55.410] – Ian

There are so many stories from this burying ground. So the second episode of God’s Little Acre will go a lot deeper. Here’s a preview.

[00:26:04.390] – Keith

We’ve got to be careful in how we interpret history. We have to base it upon the primary evidence that we have. And then if there’s gaps, we have to be very careful how we’re interpreting closing that gap. The Africans that arrived here were absolute channel properties, and we have significant numbers of runaways. We have significant numbers of brutal beatings of African men, women, and children. So, to say that New England slavery was uniquely different or better than the south or the Caribbean really doesn’t understand the system. Africans, because of the fact that they had trading and there was investments in them, significant monetary investments, they were managed more efficiently, not treated better.

[00:26:53.250] – Tonya

We’re Tonya and Ian Fitzpatrick, and we’re so happy that you’re here. It would mean a lot to us. If you would leave a five-star rating and review on Apple Podcasts or wherever you listen to World Footprints.

[00:27:06.240] – Ian

We’d love for you to join our community, so please subscribe to our bi-weekly newsletter from our website at worldfootprints.com.

[00:27:15.770] – Tonya

Thank you so much for your support and for giving us the space to share the world through the stories we offer on World Footprints.

[00:27:24.910] – Female Announcer

This World Footprints podcast with Ian and Tonya Fitzpatrick is a production of World Footprints, LLC. Silver Spring, Maryland. The multi award-winning podcast is available on worldfootprints.com and on audio platforms worldwide, including Iheart Radio, Public Radio Exchange, iTunes, and Stitcher. Connect with the world one story at a time with World Footprints. Visit worldfootprints.com to enjoy more podcasts and explore hundreds of articles from international travel writers. And be sure to subscribe to the newsletter. World Footprints is a trademark of World Footprints LLC, which retains all rights to the World Footprints portfolio, including worldfootprints.com and this podcast.